Perhaps purely motivated by profit, Somalian pirates are shuttling weapons and terrorists in and out of the country and sharing up to fifty-percent of the ransoms with al-Shabab, what it reaps from hijacking ships. Formed as the Islamic Courts Union’s (ICU) military wing, al-Shabab announced in March its affiliation with al Qaeda after regaining control of most of southern Somalia earlier this year when Ethiopia withdrew its forces.

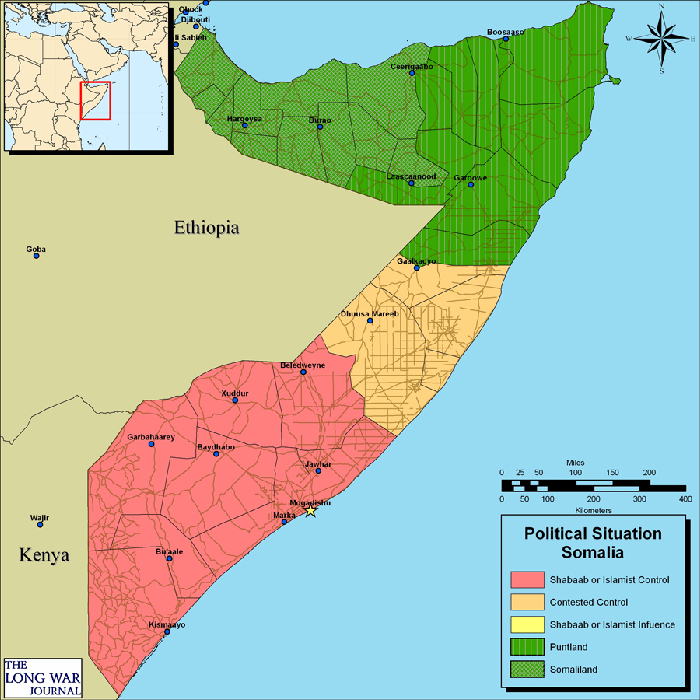

Southern Somalia is now under the control of Shabaab and other Islamist groups. Click image to enlarge. Map used with permission. Read the story at The Long War Journal

The Weekly Standard’s Thomas Joscelyn reported last month on DNI Blair’s written testimony to Congress on the US Intelligence Community’s assessment:

“We judge the terrorist threat to US interests in East Africa, primarily from al Qaeda and al Qaeda-affiliated Islamic extremists in Somalia and Kenya, will increase in the next year as al Qaeda’s East Africa network continues to plot operations against US, Western, and local targets and the influence of the Somalia-based terrorist group al Shabaab grows. Given the high-profile US role in the region and its perceived direction – in the minds of al Qaeda and local extremists – of foreign intervention in Somalia, we assess US counterterrorism efforts will be challenged not only by the al Qaeda operatives in the Horn, but also by Somali extremists and increasing numbers of foreign fighters supporting al Shabaab’s efforts.”

Joscelyn’s report continued:

Blair noted that Somalia “has not had a stable, central government for 17 years,” leaving a security vacuum filled with extremism, humanitarian crises and rampant piracy. Nor is the 2008 UN-backed agreement between the Somali Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and extremist opposition leaders likely to quell the situation, Blair surmised. In 2006, Ethiopian troops moved into Somalia in an attempt to shore up the transitional government and beat back a growing jihadist insurgency. But those forces have since receded. The withdrawal of Ethiopian troops may have “removed a key rallying point” for Shabaab, Blair noted, but “resurgent Islamic extremists are expanding their operations throughout the country.” The militants “have shifted their focus toward attacking a modest African Union peacekeeping force charged with protecting the TFG.”

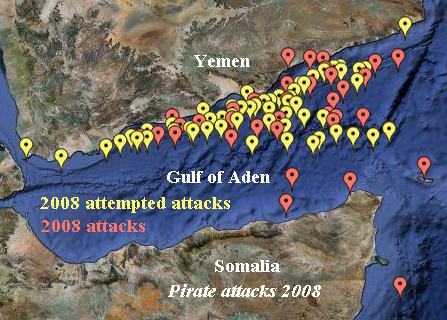

As has been widely recognized, piracy has become a major issue in the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Blair noted that the “number of successful pirate attacks has increased almost fourfold since 2007 after the pirates received several multimillion-dollar ransom payments in early 2008.” Indeed, Kenya’s foreign minister, Moses Wetangula, has claimed that pirates collected more than $150 million in ransoms during the first 11 months of 2008. The ransom demands can easily reach into the tens of millions of dollars for individual ships.

Former Ambassador David H. Shinn recently claimed there was no direct connection between the two and then immediately cited a credible source to the contrary:

Jane’s [Intelligence Review] has identified a close link between the pirates and the extremist al-Shabab group, which says it has links to al-Qaeda. The pirates in Kismayu coordinate with the al-Shabab militia in the area, although al-Shabab apparently does not play an active role in the pirate attacks. Al-Shabab requires some pirates to pay a protection fee of 5 to 10 percent of the ransom money. If al-Shabab helps to train the pirates, it might receive 20 percent and up to 50 percent if it finances the piracy operation. There is increasing evidence that the pirates are assisting al-Shabab with arms smuggling from Yemen and two central Asian countries. They are also reportedly helping al-Shabab develop an independent maritime force so that it can smuggle foreign jihadist fighters and “special weapons” into Somalia.

U.S. Navy efforts greatly reduced piracy in the Arabian Sea during 2006. Ethiopian forces invaded central and southern Somalia in late 2006 in support of the latter’s transitional government. Pirate attacks and hijackings increased during 2007, including in the Gulf of Aden. As the ICC Commercial Crime Services has charted, pirate attacks dramatically shifted to the Gulf of Aden during 2008.

Last week, that same organization reported:

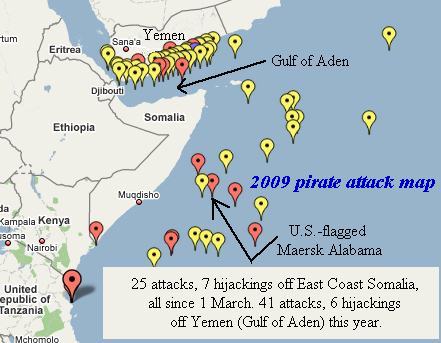

The latest incident [Maersk Alabama], early on 8 April 2009, saw the hijack of a 1,092 TEU, US-flagged container ship some 550 km off the Somalia coastline. The vessel, carrying a crew of 20, had been en route to Mombasa from Djibouti. It is the second container ship reported hijacked off Somalia in less than a week, a German-flagged and owned boxship having been captured on 5 April. According to the IMB’s Piracy Reporting Centre, there have been 25 attacks on vessels off East Coast Somalia, resulting in seven hijackings, this year — all of them since 1 March. The surge marks the return of a high volume of pirate activity in the Indian Ocean, the PRC observes. Since the beginning of April, the PRC has confirmed five attacks, with three vessels hijacked and some 74 crew taken hostage. … Last year saw a noticeable escalation in piracy focussed around the Gulf of Aden. The international community responded, and the area is now patrolled by a Task Force made up of numerous foreign navies. The initiative has resulted in a reduction in successful attacks in the region, with only six hijackings resulting from 41 attempted attacks so far in 2009. Whilst the number of attempted attacks has not significantly declined, the presence and intervention of the foreign navies has helped to prevent the vessels being hijacked.

Why the sudden shift of pirate activity to the Arabian Sea? This March 4, 2009 report by Lloyd’s of London provides some clues:

Around 90% of traffic entering the Gulf [of Aden] are following the protective corridor established by European Union naval forces but many vessels do not register their full details or voyage plans. Naval officials within EU Navfor command point out that this lack of information has hamstrung their ability to identify specific risks and offer help to the most vulnerable vessels. The protective corridor has been moved further away from Yemen’s coastline since it was first established. This was done partly to route vessels away from domestic fishing traffic but also to escape the reception area of Yemen’s mobile phone network, which UK naval officials suspect was being used to co-ordinate pirate attacks. It has also been suggested that the pirate’s motherships are using Yemen’s territorial waters to hide from naval patrols in the region.

October 29 2008, A convoy of five trucks, each carrying five boats, goes through Galkayo on its way to pirates in Hobyo. Click on image to expand it.

Galkayo serves as the logistical hub for pirates bringing in supplies from Djibouti, while Garoowe is their financial center. Click on image to enlarge.

Kenya heavily patrols its northeast border and Ethiopia blocks a spread west by al-Shabab. Yet the U.S. and all affected nations need to do much more to end piracy and the growing threat of terrorism in and off the shores of Somalia.